When a pharmacist hands you a pill bottle with a different name than what your doctor wrote, you might wonder: is this really the same thing? It’s not just a label swap. Behind every generic drug substitution is a strict, science-backed process pharmacists follow to make sure it’s safe, effective, and legally sound. This isn’t guesswork. It’s a standardized system built on decades of regulatory science and legal requirements - and pharmacists are the final gatekeepers.

The Legal Backbone: Hatch-Waxman and the Orange Book

The foundation of generic drug substitution in the U.S. comes from the Drug Price Competition and Patent Term Restoration Act of 1984 - better known as the Hatch-Waxman Act. Before this law, bringing a generic drug to market meant repeating expensive clinical trials. The act changed that by creating the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA) pathway. Generic manufacturers no longer had to prove safety and effectiveness from scratch. Instead, they had to prove one thing: equivalence. To make this practical, the FDA created the Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations - the Orange Book. First published in 1980, it’s updated monthly and is the only legal reference pharmacists are required to use when deciding whether to substitute a generic for a brand-name drug. As of April 2024, it lists over 16,500 drug products across 1,700 active ingredients. Nearly 15,900 of them carry an ‘A’ rating - meaning they’re considered therapeutically equivalent to their brand-name counterpart.Three Layers of Equivalence: What Pharmacists Check

Pharmacists don’t just look at the name on the bottle. They verify three levels of equivalence before swapping a drug:- Pharmaceutical equivalence - The generic must have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form (tablet, capsule, injection), and route of administration as the brand. No hidden fillers or different release mechanisms allowed.

- Bioequivalence - This is where science kicks in. The generic must deliver the same amount of drug into your bloodstream at the same rate as the brand. The FDA requires that the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of peak concentration (Cmax) and total exposure (AUC) between generic and brand falls between 80% and 125%. For high-risk drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, the window tightens to 90-111%.

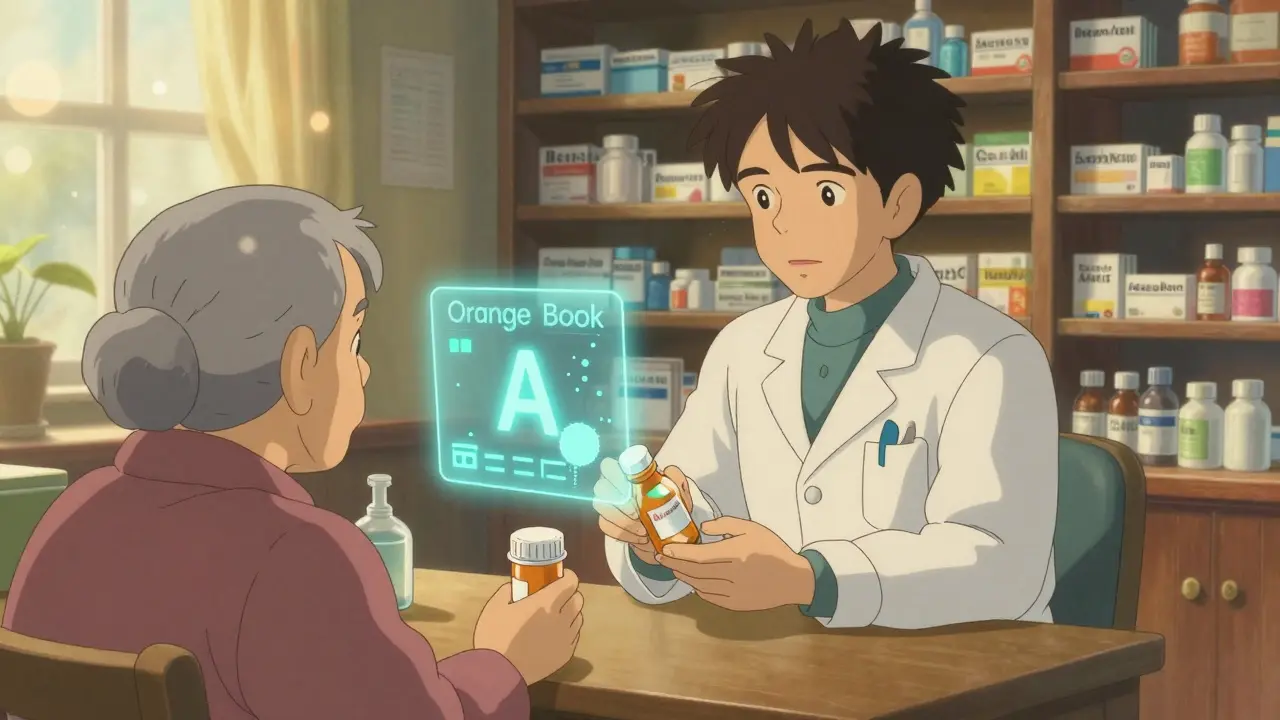

- Therapeutic equivalence - This is the final call. If a drug passes both pharmaceutical and bioequivalence tests, it gets an ‘A’ rating in the Orange Book. That means it’s not just chemically similar - it’s clinically interchangeable.

The Orange Book Code System: What the Letters Mean

The Orange Book uses a two-letter code to tell pharmacists what they’re dealing with. The first letter is the key:- A - Therapeutically equivalent. Safe to substitute.

- B - Not equivalent. Don’t substitute.

- AB - The most common rating. Proven bioequivalent through human studies. Over 98.7% of rated products fall into this category.

- AN - Aerosol nasal products.

- AO - Oral solutions.

- AT - Topical products.

How Pharmacists Actually Do It - Day to Day

You might think checking the Orange Book is a time-consuming task. It’s not. Time-motion studies show pharmacists spend just 8 to 12 seconds per prescription verifying equivalence. Here’s the routine:- Find the brand-name drug in the system - that’s the Reference Listed Drug (RLD).

- Check the Orange Book for all generics approved as equivalent to that RLD.

- Confirm the generic has an ‘A’ rating and matches the active ingredient, strength, and dosage form.

- Look for any ‘Do Not Substitute’ notes from the prescriber.

What Happens When the Orange Book Doesn’t List a Drug?

About 5.7% of generic substitutions involve drugs not yet in the Orange Book. This happens with new generics, complex formulations like inhalers or topical creams, or drugs where bioequivalence studies are still under review. In these cases, pharmacists follow FDA’s Non-Orange Book Listed Drugs guidance. They don’t guess. They consult prescribing information, contact the manufacturer, or check for published bioequivalence data. If there’s no clear evidence, they dispense the brand-name drug - or consult the prescriber.

Why This System Works - And Why It’s Still Evolving

The system isn’t perfect, but it’s proven. A 2020 FDA meta-analysis found the rate of adverse events after switching from brand to generic was statistically identical: 0.78% vs. 0.81%. A 2023 study of over 2,100 bioequivalence trials showed most generics differed from brands by less than 5% in drug exposure - far inside the 80-125% safety window. But challenges remain. Complex drugs - like inhalers, injectables, and topical creams - don’t always behave the same way in the body even if blood levels match. Dr. Randall Stafford of Stanford pointed out in a 2021 JAMA commentary that traditional bioequivalence metrics might miss real-world differences in these products. In response, the FDA has developed product-specific guidances for over 1,850 complex drugs and allocated $28.5 million through GDUFA III to improve testing methods. Biosimilars - the biologic version of generics - are another frontier. As of June 2024, only 47 of 350 approved biosimilars are listed in the FDA’s Purple Book (the biologics equivalent of the Orange Book). Pharmacists are still learning how to verify these, and many prescribers don’t yet understand the difference between biosimilars and generics.The Bigger Picture: Why It Matters

Generic drugs now make up 90.7% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S. - 8.9 billion prescriptions in 2023. That’s $12.7 billion in annual savings for patients and the healthcare system. But none of that matters if the substitution isn’t safe. The Orange Book system isn’t just a tool. It’s a legal shield for pharmacists and a guarantee for patients. When a pharmacist checks that ‘A’ rating, they’re not just following procedure. They’re preventing harm, reducing costs, and ensuring every patient gets the same therapeutic outcome - no matter what the label says.Training and Competency: Making Sure Everyone Gets It Right

New pharmacists don’t just learn this on the job. Pharmacies require formal training during orientation - typically 2 to 4 hours focused on the Orange Book, substitution laws, and common pitfalls. After training, competency assessments show 89.3% accuracy in equivalence verification. That’s not luck. It’s deliberate, standardized education. And it’s working. The National Community Pharmacists Association reports substitution error rates of just 0.03% when the system is followed correctly. That’s one mistake in every 3,300 prescriptions.Can a pharmacist substitute a generic without the prescriber’s permission?

Yes - but only if the drug is listed in the FDA Orange Book with an ‘A’ therapeutic equivalence rating and the prescriber hasn’t written ‘Dispense as Written’ or ‘No Substitution’ on the prescription. All 49 states (except Massachusetts) allow automatic substitution under these conditions. Pharmacists must still check the prescription label and confirm the patient hasn’t objected.

Are all generic drugs the same?

No - not all generics are created equal, but all approved generics that carry an ‘A’ rating in the Orange Book are considered therapeutically equivalent. That means they meet the same strict standards for active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and bioavailability. Differences in inactive ingredients (like fillers or dyes) don’t affect safety or effectiveness, and are allowed.

Why do some people say generics don’t work as well?

Most reports of generics ‘not working’ are due to placebo effects, changes in pill appearance, or unrelated health changes. Clinical studies show no meaningful difference in outcomes between brand and generic drugs. For narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, some patients may need closer monitoring after switching - not because the generic is less effective, but because small changes in blood levels matter more in these cases.

Is the Orange Book the only source pharmacists can use?

Legally, yes. While pharmacists may use commercial databases like Micromedex or Lexicomp for convenience, only the FDA Orange Book is recognized by state pharmacy boards as the official standard for therapeutic equivalence. Substituting based on any other source - even if the drug seems equivalent - can expose the pharmacist to legal liability.

What happens if a generic isn’t in the Orange Book yet?

If a generic isn’t listed, pharmacists cannot substitute it automatically. They must dispense the brand-name drug unless they can confirm bioequivalence through FDA-issued product-specific guidances, manufacturer data, or direct consultation with the prescriber. In these cases, the pharmacist’s professional judgment - backed by documentation - is critical.

15 Comments

Christina Widodo-12 January 2026

So basically, the system works because pharmacists aren’t just guessers-they’re forensic chemists with a checklist? That’s wild. I always thought it was just about price.

Turns out, my pill swap is backed by math, law, and a 40-year-old government database. Mind blown.

Alice Elanora Shepherd-13 January 2026

I’ve worked in community pharmacy for 22 years. The Orange Book isn’t just a reference-it’s our legal armor. One time, a patient demanded a generic for a drug that wasn’t listed. I refused. They yelled. I called the prescriber. They changed their mind. That’s the job.

People think we’re just label-swappers. We’re not. We’re the last line between a patient and a bad outcome.

And yes-I use the FDA app. It’s free, reliable, and doesn’t require a subscription. Why pay for anything else?

steve ker-14 January 2026

Why do you even care? It’s a pill. If it looks like the same color and shape it’s fine. Stop overthinking. The system is just corporate control disguised as science.

Also why is everyone in the US obsessed with databases? We don’t need a 16k-entry list to take medicine.

Sonal Guha-15 January 2026

Let’s be real-the 80-125% bioequivalence window is a joke. That’s a 45% swing. You’d never accept that kind of variance in a car engine or a bridge. But for your heart medication? Sure, whatever.

And don’t even get me started on the ‘A’ rating. It’s not a guarantee. It’s a loophole with a fancy name.

gary ysturiz-15 January 2026

This is actually one of the most reassuring things I’ve read all week. So many people think generics are cheap knockoffs. But this? This is science done right.

Pharmacists are heroes. They check a code in 10 seconds and protect thousands of people every day. We should be thanking them, not complaining about pill colors.

Also-90.7% of prescriptions are generics? That’s huge. And safe. That’s a win.

Monica Puglia-16 January 2026

OMG I just realized I’ve been taking generics for 12 years and never once thought about this 😭

Thank you for explaining. I’m now 100% more confident in my blood pressure med. And also, I’m going to hug my pharmacist next time I see them. 🤗💊

Alex Fortwengler-16 January 2026

Yeah right. The Orange Book is a government lie. Big Pharma owns the FDA. They let generics in so they can keep charging for the brand version. The ‘A’ rating? Just a marketing tool.

I’ve seen people get sick after switching. You think that’s coincidence? No. It’s a cover-up.

And don’t even mention the ‘non-Orange Book’ drugs-that’s where the real danger is. They’re dumping untested crap on us and calling it ‘equivalent’.

Daniel Pate-16 January 2026

The real question isn’t whether generics work-it’s why we need a 40-year-old legal framework to verify what should be basic pharmacology.

Why isn’t bioequivalence data open-source? Why can’t independent labs validate equivalence without relying on a single government database?

This system works-but it’s fragile. And it shouldn’t be this opaque. Transparency isn’t a luxury. It’s a requirement for public trust.

Windie Wilson-18 January 2026

So let me get this straight: I pay $15 for a brand-name pill, but my pharmacist gives me a $3 generic… and somehow, it’s the same thing? Because science?

Meanwhile, my iPhone charger from Walmart explodes if I look at it funny.

Why does my medication get the benefit of the doubt but my electronics get the death penalty?

Also, who named it the ‘Orange Book’? Was there a ‘Blue Book’? A ‘Purple Book’? Did someone just grab the first colored binder they found?

Jessica Bnouzalim-20 January 2026

As someone who takes 7 meds a day-5 of them generics-I need to say this: I used to panic every time the pill looked different.

Now I know why. And I’m not scared anymore. Thank you for making this so clear.

Also, pharmacists? You’re the real MVPs. I’m bringing you cookies next week. 🍪❤️

Rebekah Cobbson-21 January 2026

Thank you for this. I’m a nurse, and I’ve seen patients refuse generics because they ‘don’t trust them.’ This is exactly what I need to share with them.

It’s not about fear-it’s about lack of information. This post gives people the facts, not the fear.

And yes, I’ll be printing this out for our patient education folder.

Jennifer Phelps-22 January 2026

Wait so if a drug isn't in the Orange Book you can't substitute it even if it's the same exact thing

What if the manufacturer just hasn't submitted the paperwork yet

That seems like a huge bottleneck

Amanda Eichstaedt-23 January 2026

I love how this system treats patients like rational adults who deserve to know what’s in their body.

Not like the rest of healthcare where you get a pill and a shrug.

Pharmacists are the only ones who treat you like a human with a right to understand.

And the Orange Book? It’s not bureaucracy. It’s respect.

Also-98.7% accuracy? That’s better than most tech companies. We should be building apps like this.

TiM Vince-23 January 2026

Just read this on my lunch break. Didn’t expect to get emotional.

My mom died because she couldn’t afford her brand-name meds. She took the generic. She was fine for years. Then one day, something changed. We never knew why.

This post doesn’t erase that pain. But it helps me understand it wasn’t the generic’s fault.

Thank you.

Audu ikhlas-23 January 2026

USA thinks its system is perfect but in Nigeria we just give pills and hope for the best. You have your Orange Book we have our prayer book.

Also why are you all so obsessed with FDA? In Africa we trust our doctors not databases. Your system is weak because it needs paper and phones. We have faith.