When you take a pill for high blood pressure, you expect every tablet to be exactly the same. That’s because small-molecule drugs are made through chemical reactions - they’re like stamped metal parts. But if you’re on a biologic for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, or cancer, what’s in your injection isn’t a single molecule. It’s a soup of millions of slightly different versions of the same protein. And each batch - or lot - of that medicine can vary a little. This isn’t a mistake. It’s normal. It’s called lot-to-lot variability.

Why biologics aren’t like generics

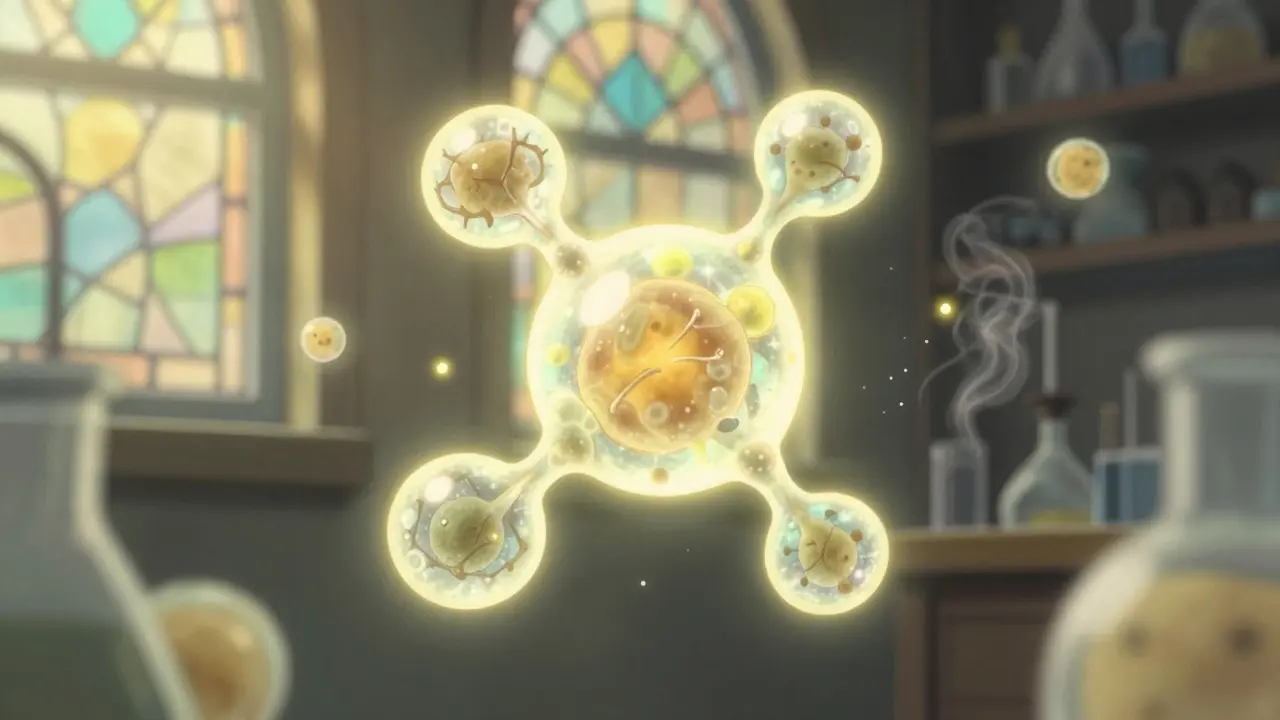

People often think biosimilars are just cheaper versions of brand-name drugs, like how generic aspirin is the same as brand-name aspirin. That’s not true. Generics are exact copies of small-molecule drugs. Their chemical structure is simple and identical from batch to batch. If you dissolve two pills, you get the same molecules every time. Biologics are different. They’re made inside living cells - yeast, bacteria, or mammalian cells. These cells act like tiny factories. Even under perfect conditions, no two batches will be exactly alike. The cells might attach slightly different sugar molecules (glycosylation), change the shape of a protein fold, or add extra amino acids. These tiny differences are called post-translational modifications. They happen naturally. The FDA says a single lot of a biologic can contain millions of slightly different versions of the same protein. That’s why biosimilars aren’t called “generics.” They’re called biosimilars - highly similar, but not identical. The FDA makes this clear: “Biosimilars Are Not Generics.” You can’t just swap them like you would with a generic pill. There’s a whole different approval process.How regulators handle the variation

The FDA doesn’t ignore lot-to-lot variability. They expect it. In fact, they require manufacturers to prove they can control it. For a biosimilar to get approved, the company must show their product’s variation pattern matches the original reference biologic - not just in overall structure, but in the range and type of minor differences. This isn’t done with one test. It’s done with hundreds. Analytical studies look at things like protein folding, sugar attachments, charge variants, and impurity profiles. These tests are so sensitive they can detect differences smaller than a single atom. If the biosimilar’s lot-to-lot variation falls within the same range as the reference product, that’s a good sign. Then comes clinical testing. Even if the chemistry looks right, the FDA wants to see that patients respond the same way. Does it lower inflammation? Does it shrink tumors? Does it cause the same side effects? If the answer is yes - and there’s no clinically meaningful difference - the biosimilar gets approved. For a biosimilar to be labeled interchangeable, the bar is even higher. The manufacturer must prove that switching back and forth between the reference product and the biosimilar doesn’t increase risk or reduce effectiveness. That means running studies where patients alternate between the two drugs over months. Only 12 out of 53 approved biosimilars in the U.S. as of May 2024 have this designation.What this means for labs and testing

Lot-to-lot variability doesn’t just affect patients. It hits laboratories hard. If you’re running a blood test for HbA1c (a diabetes marker), the reagent you use can change between lots. A 2022 survey found that 78% of lab directors see this as a major challenge. Here’s the problem: quality control samples (QC) don’t always behave the same way as real patient samples. A new reagent lot might show perfect QC numbers but give different results for actual patients. One lab reported a 0.5% average increase in HbA1c results after switching lots - enough to push a patient from “well-controlled” to “poorly controlled” diabetes. To catch this, labs use methods like moving averages - tracking patient results over time to spot drift. They also test 20 or more patient samples with duplicates when switching reagent lots. This isn’t optional. It’s a safety step. A single undetected shift can lead to wrong diagnoses or incorrect treatment adjustments. Smaller labs struggle the most. Verifying a new reagent lot can take 15-20% of a technician’s time each quarter. And there’s no easy fix. The tools are expensive. The protocols are complex. But skipping verification? That’s not an option.

Why variability isn’t a flaw - it’s a feature

Some doctors worry that variability means biologics are unreliable. But experts say the opposite. This natural variation is what makes these drugs possible. Think about it: you can’t chemically synthesize a monoclonal antibody the way you make ibuprofen. The structure is too complex. The only way to make these drugs is to use living cells. And living systems are messy. They’re not machines. They’re alive. The key isn’t eliminating variation - it’s understanding and controlling it. The FDA’s approach is called the “totality of the evidence.” They don’t look at one test. They look at everything: analytical data, animal studies, clinical trials, manufacturing controls. If the whole picture shows consistent safety and effectiveness, the product passes. Dr. Sarah Y. Chan from the FDA puts it simply: “Inherent variations occur in both reference products and biosimilars. These slight differences… are normal and expected.”What’s changing in 2026

The field is moving fast. New technologies like high-throughput mass spectrometry and AI-driven analytics are making it easier to map and predict lot-to-lot differences. By 2026, experts predict 70% of new biosimilar applications will include data on interchangeability - up from 45% in 2023. The market is growing too. The global biosimilars market hit $10.6 billion in 2023 and is projected to hit $35.8 billion by 2028. More than a third of all biologic prescriptions in the U.S. are now filled with biosimilars. Companies like Amgen, Pfizer, and Sandoz are racing to bring more options to market. Even complex therapies like antibody-drug conjugates and cell and gene therapies are on the horizon. These will have even more variability than today’s biologics. The lessons learned from managing lot-to-lot variation in monoclonal antibodies are becoming the blueprint for the next generation of medicines.

10 Comments

Jake Moore-18 January 2026

Just worked a 16-hour shift in the lab switching reagent lots last week. One batch gave us a 0.7% spike in HbA1c across 40 patient samples. We caught it because we ran duplicates, but holy crap - if we hadn’t, someone might’ve been put on insulin they didn’t need. This stuff isn’t theoretical. It’s daily reality for us front-line techs.

Nishant Sonuley-18 January 2026

You know what’s wild? In India, we don’t even have the luxury of high-throughput mass spec or AI-driven analytics - we’re still fighting to get basic QC protocols standardized across regional labs. And yet, somehow, we manage. We track patient trends with Excel sheets and hope for the best. I’ve seen a technician cry because a new lot of rituximab caused a 12% drop in CD20 counts - not because the drug was bad, but because the glycosylation pattern shifted slightly. We don’t call it ‘lot-to-lot variability’ here. We call it ‘survival mode.’ And somehow, we still save lives.

Emma #########-19 January 2026

I’m a rheumatology nurse. Last year, a patient switched from Humira to a biosimilar and said she felt ‘off’ - more fatigue, joint stiffness returning. We didn’t panic. We tracked her labs, gave her time, and kept communication open. Three weeks later, she was back to baseline. It’s not about fear. It’s about listening. The system works - but only if we don’t treat patients like data points.

Andrew McLarren-20 January 2026

It is imperative to underscore that the regulatory framework governing biosimilars represents a paradigm of scientific rigor and prudence. The totality of evidence approach, as articulated by the FDA, ensures that clinical outcomes remain uncompromised despite inherent biological variability. This is not an exception to pharmaceutical excellence - it is its evolution.

Andrew Short-22 January 2026

Oh, so now it’s ‘a feature of life itself’? That’s just corporate speak for ‘we can’t control it, so we’ll call it natural.’ You know what else is ‘natural’? Contaminated batches. You think the FDA checks every lot? They don’t. They approve based on a few cherry-picked samples. And then they wonder why people get sick after switching. This isn’t science - it’s a gamble with your life, and they’re betting you won’t notice until it’s too late.

Danny Gray-22 January 2026

Wait - so if living cells are ‘messy,’ then why are we even trying to replicate them? Why not just accept that biology is unpredictable and develop synthetic alternatives? Or maybe - and hear me out - maybe the entire biologics model is just capitalism exploiting the complexity of life to charge $200K per year for something that shouldn’t even exist in this form. We’re treating proteins like they’re iPhones. They’re not. They’re alive. And we’re trying to mass-produce soul.

Tyler Myers-24 January 2026

They’re lying. The FDA’s ‘totality of evidence’? That’s just a cover. I’ve seen the internal memos. The real reason biosimilars are approved is because Big Pharma bribes regulators to clear them so they can kill off competition - then jack up the price of the original. And labs? They’re forced to use the cheapest reagent because insurance won’t cover the ‘brand’ version. That’s why HbA1c numbers jump - it’s not variability. It’s corruption. And they’re hiding it behind science jargon.

Praseetha Pn-25 January 2026

Y’all act like this is some groundbreaking revelation. In Mumbai, we’ve been fighting this since 2015. One batch of trastuzumab made half the patients break out in hives. The lab said ‘within acceptable variance.’ I said, ‘Then why did 12 women stop breathing?’ We had to source the original from Germany - at triple the cost - just to keep people alive. This isn’t science. It’s a lottery. And the only ones winning are the CEOs in Zurich.

Chuck Dickson-25 January 2026

Big picture: this is why biosimilars are the future. Yeah, it’s complex. Yeah, it’s messy. But we’re making life-saving drugs affordable for millions who couldn’t afford them before. The system’s not perfect - but it’s improving. Every new analytical tool, every lab protocol, every patient report - it all helps. Keep pushing. Keep testing. Keep speaking up. We’re building something real here.

Naomi Keyes-26 January 2026

It is critical to note, however, that the notion of ‘natural variation’ is fundamentally misleading - and potentially dangerous - when applied to pharmaceuticals intended for human use. The FDA’s acceptance of ‘millions of slightly different versions’ of a protein as ‘normal’ constitutes a radical departure from the foundational principles of pharmacology - which demand consistency, reproducibility, and predictability. This is not innovation - it is institutionalized negligence, masked as pragmatism.