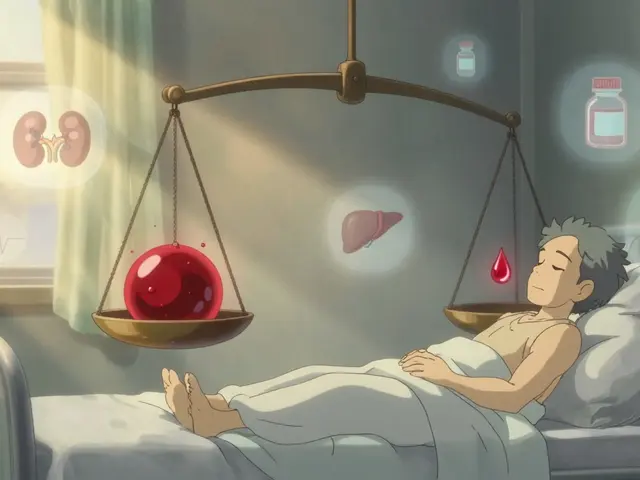

When you take an ACE inhibitor for high blood pressure or heart failure, and your doctor adds a potassium-sparing diuretic to help with fluid retention, it might seem like a smart combo. But here’s the catch: this combination can push your potassium levels into dangerous territory. Hyperkalemia - when potassium in your blood climbs above 5.0 mmol/L - doesn’t always cause symptoms. By the time you feel your heart racing or your muscles weak, it might already be too late. This isn’t a rare side effect. It’s a predictable, well-documented, and often overlooked risk that affects millions.

How ACE Inhibitors and Potassium-Sparing Diuretics Work Together - and Why That’s Dangerous

ACE inhibitors like lisinopril, enalapril, or ramipril work by blocking a hormone called angiotensin II. That helps relax blood vessels and lower blood pressure. But there’s a side effect you don’t hear much about: less aldosterone. Aldosterone is the hormone that tells your kidneys to flush out extra potassium. When ACE inhibitors cut aldosterone, potassium stays in your body.

Potassium-sparing diuretics - spironolactone, eplerenone, amiloride, triamterene - do something similar but through different paths. Spironolactone and eplerenone block aldosterone receptors directly. Amiloride and triamterene shut down sodium channels in the kidney that normally help push potassium out. So both types of drugs reduce potassium excretion. Put them together? You get a double hit. Your kidneys stop working as hard to clear potassium. And if you have kidney problems, heart failure, or diabetes, your body doesn’t have much backup.

Studies show this combo isn’t just risky - it’s significantly riskier than either drug alone. A 1998 study in JAMA found that 11% of patients on ACE inhibitors alone developed hyperkalemia. When you add a potassium-sparing diuretic, that number jumps to over 30%. The REIN study showed that in patients with kidney disease, hyperkalemia went from 4.2% with ACE inhibitors alone to 18.7% when spironolactone was added.

Who’s Most at Risk - And Why It’s Not Just About the Drugs

Not everyone on this combo will get hyperkalemia. But some people are walking into a storm without a raincoat. The biggest risk factors aren’t the drugs themselves - they’re your body’s condition.

- eGFR below 60 mL/min/1.73m²: If your kidneys aren’t filtering well, they can’t excrete potassium efficiently. This alone adds 2 points to your hyperkalemia risk score.

- Baseline potassium above 4.5 mmol/L: If your potassium is already creeping up before you start the combo, you’re closer to the danger zone.

- Diabetes or heart failure: Both conditions mess with how your body handles potassium. Diabetes damages kidney function over time. Heart failure triggers hormonal changes that retain potassium.

- Older age: Kidney function naturally declines after 60. And many older adults are on multiple medications that add to the risk.

One study found that 78% of hyperkalemia cases happen within the first three months of starting this drug combo. The peak? Weeks 4 to 6. That’s when your body has fully adjusted to the drugs - and potassium has started to build up.

What Happens When Potassium Gets Too High

Hyperkalemia doesn’t always cause warning signs. Some people feel nothing until their heart rhythm goes haywire. At levels above 6.0 mmol/L, you’re at risk of life-threatening arrhythmias - including ventricular fibrillation and cardiac arrest.

But even before that, you might notice:

- Muscle weakness or fatigue

- Numbness or tingling in hands or feet

- Nausea or irregular heartbeat

- Feeling unusually short of breath

These symptoms are easy to ignore. They look like aging, stress, or just being tired. But if you’re on this drug combo, they’re red flags. A simple blood test - serum potassium - is the only way to know for sure.

Why Doctors Often Miss This - And What You Can Do

Here’s the ugly truth: even though guidelines are clear, most patients aren’t monitored properly. A 2016 study found that only 57% of patients with hyperkalemia had their potassium rechecked within 30 days. And one-third of those with severe hyperkalemia (above 6.0 mmol/L) had no follow-up at all within a week.

Why? Many doctors assume the patient is fine if they feel okay. Or they’re worried about stopping life-saving drugs like ACE inhibitors. But here’s the twist: stopping RAAS inhibitors after hyperkalemia happens isn’t always the right move. These drugs reduce death risk by 23% in heart failure and 26% after a heart attack. You don’t want to quit them unless you have a plan to manage the potassium.

What you should ask your doctor:

- “What’s my current potassium level?”

- “When was the last time I had it checked?”

- “Do I need a repeat test in the next 1-2 weeks?”

- “Is there a safer alternative to this combo?”

Don’t wait for symptoms. Get tested.

What to Do If Your Potassium Is High

If your potassium is above 5.0 mmol/L, don’t panic - but do act. Here’s what works:

- Check your diet. Bananas, oranges, potatoes, tomatoes, spinach, and dried fruit are packed with potassium. Many processed foods have added potassium chloride as a salt substitute. That can add 1,000-2,000 mg of extra potassium daily without you knowing. Cutting back can lower your levels by 0.3-0.6 mmol/L.

- Switch to a non-potassium-sparing diuretic. Hydrochlorothiazide or furosemide can help your kidneys flush out potassium. Studies show adding a thiazide diuretic cuts potassium by 0.5-1.0 mmol/L within two weeks.

- Reduce the ACE inhibitor dose. Sometimes halving the dose (e.g., from 20 mg to 10 mg of lisinopril) is enough to bring potassium down without losing blood pressure control.

- Consider switching to an ARB. Angiotensin receptor blockers like losartan or valsartan cause about 18% less hyperkalemia than ACE inhibitors, according to research. They’re not risk-free, but they’re often better tolerated.

- Ask about potassium binders. New drugs like patiromer (Veltassa) and sodium zirconium cyclosilicate (Lokelma) bind potassium in the gut and remove it in stool. They let you keep your heart medications while keeping potassium safe. In trials, 89% of patients who used them could stay on their RAAS inhibitors.

The European Heart Journal found that only 32% of patients with hyperkalemia get dietary counseling. That’s a huge gap. You can’t fix this with pills alone.

The Real Cost - And Why This Matters More Than You Think

Hyperkalemia isn’t just a lab value. It’s expensive. In the U.S., each hospitalization for hyperkalemia costs an average of $11,200. Annually, it adds up to $4.8 billion. And it’s preventable.

More than 45 million Americans take ACE inhibitors. About 12 million of them are also on potassium-sparing diuretics. That’s 5.4 million people at high risk. And yet, only 28% of primary care doctors follow the recommended monitoring schedule. Most don’t even know the guidelines.

Here’s what’s changing: newer tools are emerging. SGLT2 inhibitors like dapagliflozin (used for diabetes and heart failure) have been shown to reduce hyperkalemia risk by 32% in patients on ACE inhibitors. Digital apps that track dietary potassium are cutting episodes by 27%. Point-of-care potassium testing devices are in trials and could soon let you check your levels at home.

But until then, the simplest, most effective tool is still the blood test - and knowing your numbers.

Bottom Line: Stay Informed, Stay Alive

ACE inhibitors and potassium-sparing diuretics save lives. But they can also kill if potassium isn’t watched. The risk isn’t random. It’s predictable. It’s preventable. And it’s happening to thousands of people right now - quietly, without symptoms.

If you’re on this combo:

- Get your potassium checked within 1 week of starting - not at your next annual checkup.

- Know your eGFR. If it’s below 60, you need monthly checks for the first 3 months.

- Ask about alternatives: ARBs, lower doses, or thiazide diuretics.

- Track your diet. Avoid high-potassium foods unless your doctor says otherwise.

- Don’t assume you’re fine because you feel fine.

Hyperkalemia doesn’t shout. It whispers. And if you’re not listening - it could be the last thing you hear.

1 Comments

Tasha Lake- 7 February 2026

So the ACEi + spironolactone combo is basically a potassium time bomb, huh? I get that aldosterone suppression is the core mechanism, but have we looked at the interplay with RAAS rebound post-discontinuation? I’ve seen cases where patients get rebound hyperkalemia even after switching to ARBs because their renin spikes like a Jackson Pollock painting. Also-what’s the data on potassium binders in real-world primary care? Most studies are RCTs in tertiary centers. In the real world, adherence to Veltassa is trash. Cost, dosing, and that chalky texture make it a nonstarter for 60% of my elderly patients.

And don’t even get me started on the sodium zirconium cyclosilicate trials. They show great efficacy, but the FDA’s black box warning for fluid overload in NYHA Class III/IV HF? That’s a dealbreaker for a lot of cardiologists. We’re stuck between a rock and a hard place.

Also-why is no one talking about the role of gut microbiota in potassium excretion? Emerging data suggests butyrate-producing flora modulate ENaC channels. Could probiotics be an adjuvant? Just throwing it out there.