Across the world, millions of people rely on generic drugs to manage chronic conditions like high blood pressure, diabetes, and depression. These medications are chemically identical to their branded counterparts but cost a fraction of the price. Yet how countries make generics work - and whether they actually succeed - varies wildly. Some systems slash prices so hard that manufacturers can’t stay in business. Others create complex rules that delay competition. And in a few places, the system works so well that 90% of prescriptions are filled with generics, saving billions every year.

The core idea is simple: when a drug’s patent expires, other companies should be able to make the same medicine and sell it cheaper. But in practice, that’s where things get messy. The U.S., Europe, China, India, and South Korea all have radically different approaches. And each one has winners and losers - patients, manufacturers, and healthcare systems caught in the middle.

How the U.S. Got 90% Generic Use - and Why It Still Pays More

The United States leads the world in generic drug use. Nearly 90.1% of all prescriptions filled are for generics. That’s higher than Canada, Germany, or the UK. But here’s the twist: even with that kind of adoption, the U.S. still has some of the highest drug prices in the world.

Why? Because generics don’t fix the problem of expensive brand-name drugs. While a generic version of a blood pressure pill might cost $4 a month, the branded version still sells for $120. Medicare saved $142 billion in 2025 alone thanks to generics - $2,643 per beneficiary. But those savings are only possible because the government negotiates hard with manufacturers. The FDA’s Orange Book lists over 11,342 approved generic products. And for new generics with no competition, the FDA offers a special “Competitive Generic Therapy” (CGT) designation. This gives the first company to file a 180-day exclusivity period, which speeds up entry. Zenara Pharma’s Sertraline Hydrochloride capsules, approved in August 2025, are a perfect example - they hit the market faster thanks to this system.

But there’s a dark side. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) - the middlemen between insurers and pharmacies - sometimes charge patients more for generics than for brand-name drugs. Reddit users on r/AskDocs reported that 63% of people have been hit with higher copays for generics. It’s not about the drug. It’s about the business model.

Europe’s Broken Promise: Same Drug, 300% Price Difference

Europe has a system built on unity - but it’s anything but unified. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) approves generics for all 27 member states. But then? Each country sets its own price. The result? A patient in Germany might pay €2 for a generic statin. The same pill costs €8 in Italy. In some cases, the price difference exceeds 300%.

This isn’t a bug - it’s a feature. Countries like the Netherlands use “external reference pricing,” meaning they look at what other nations pay and set their price even lower. They compare prices in France, Belgium, the UK, and even Norway - not just EU countries - to squeeze out the best deal. It works. But it also creates chaos. Manufacturers can’t plan. Pharmacists can’t predict. And patients get confused.

Germany leads in generic use at 88.3% by volume. Italy? Only 67.4%. Why? It’s not about wealth. It’s about policy. Germany mandates that pharmacists substitute generics unless the doctor says no. Italy doesn’t. Simple as that. The OECD calls this a “bifurcated market” - the same drug, two completely different realities.

China’s Billion-Dollar Bet: Price Cuts So Deep They Break Manufacturers

China’s Volume-Based Procurement (VBP) policy is the most aggressive generic pricing system ever tried. Starting in 2018, the government began buying drugs in bulk - not just one hospital, but entire provinces. They held public bidding. The lowest price won. And won big - the entire hospital’s demand, guaranteed.

The results? Average price drops of 54.7%. In some cases, like certain diabetes drugs, prices fell by 93%. By 2025, the program covered over 500 drugs. It’s why 89% of Chinese patients say their out-of-pocket costs dropped by 63%.

But here’s what no one talks about: 23% of manufacturers report losing money on VBP contracts. They’re selling at prices below their cost to make the drug. Some have shut down production lines. In 2024, Amlodipine besylate - a common blood pressure pill - vanished from 12 provinces for six to eight weeks because no one could make it profitably. Patients got sick. Hospitals scrambled.

China’s system works for affordability. But it’s not sustainable. If manufacturers can’t survive, who will make the next generic?

India: The World’s Pharmacy - But Quality Is a Gamble

India makes 20% of the world’s generic drugs by volume. That’s more than any other country. It’s why you can buy a year’s supply of generic antibiotics for under $5. It’s also why the FDA issued over 2,000 import alerts in 2024 - up from 1,247 in 2020.

India’s secret? Compulsory licensing. Under Section 84 of its Patents Act, the government can allow local companies to copy patented drugs without permission if they’re too expensive. That’s how India became the go-to source for HIV meds, cancer drugs, and vaccines for low-income countries.

But quality control is uneven. A 2025 study in the Lancet found a 17% rise in FDA warning letters to Indian manufacturers for data integrity issues - falsified lab results, missing records, unverified tests. Indian doctors on MedIndia Network report that 58% of them worry about bioavailability in generics for epilepsy and blood thinners. One pill might work. The next might not. It’s not about intent. It’s about pressure. Cut costs too far, and corners get cut.

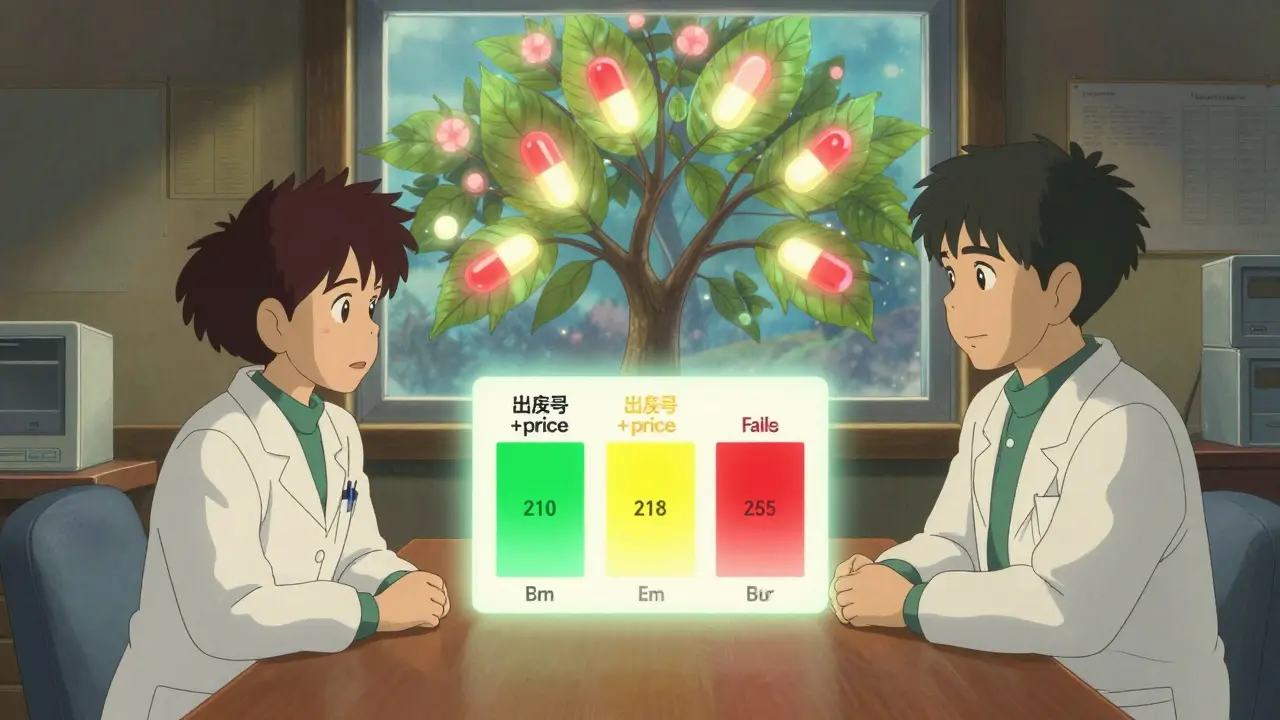

South Korea’s Tightrope: Fewer Generics, Better Prices

South Korea didn’t try to flood the market with generics. It tried to control them. In 2020, it launched the “1+3 Bioequivalence Policy.” Only three generic versions of any drug can be approved - and they must all use the same bioequivalence data. No more 20 versions of the same pill.

Then came the “Differential Generic Pricing System.” If a generic meets both quality and price standards? It sells at 53.55% of the brand’s price. If it meets only one? 45.52%. If it fails both? 38.69%. This isn’t just about cost. It’s about incentives.

The result? Between 2020 and 2024, redundant generic entries dropped by 41%. New launches fell by 29%. But prices stabilized. Patients paid less. Manufacturers made more. It’s the rare case where regulation didn’t crush competition - it sharpened it.

What Works? What Doesn’t?

There’s no perfect system. But some patterns stand out:

- Transparency works. When prices are public and rules are clear, manufacturers plan better. South Korea and the Netherlands prove this.

- Price cuts that ignore cost = shortages. China’s VBP saved money - but nearly broke supply chains.

- Pharmacist education boosts adoption. Studies show that when pharmacists explain generics to patients, acceptance jumps by 22-35%.

- Manufacturing quality can’t be an afterthought. The FDA’s import alerts aren’t random. They’re a warning.

The WHO recommends a minimum 15-20% gross margin for manufacturers. Why? Because if they can’t cover costs, they stop making drugs. That’s not a profit issue. It’s a public health risk.

The Future: More Patents Expire - But Will Systems Be Ready?

Between 2025 and 2030, over $200 billion in branded drug sales will lose patent protection. That’s a chance to save even more. But only if policies adapt.

The U.S. Inflation Reduction Act will let Medicare negotiate prices on 10-20 high-cost drugs starting in 2028. That could push even more patients to generics. The EU’s new Pharmaceutical Package, expected in late 2025, might finally align pricing rules across borders. China’s VBP expansion in January 2026 will include 150 more drugs - with prices 65% below current levels.

But if every country keeps trying to win by cutting prices to zero, we’ll end up with fewer manufacturers, worse quality, and empty shelves. The goal isn’t to make generics cheap. It’s to make them sustainable.

Are generic drugs really as effective as brand-name drugs?

Yes - if they’re made properly. Generic drugs must meet strict bioequivalence standards: their active ingredient must deliver the same amount of medicine into the bloodstream within 80-125% of the brand’s performance. The FDA, EMA, and WHO all require this. But in places with weak oversight, like some Indian or African manufacturers, quality control can slip. That’s why regulatory inspections and import alerts matter. A generic from a reputable manufacturer is just as safe and effective. One from an unverified source? Not always.

Why do some insurance plans charge more for generics than brands?

It’s not about the drug - it’s about the middlemen. Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) negotiate rebates with drug makers. Sometimes, they get bigger rebates from brand-name companies than from generics. To keep those rebates, they structure copays so patients pay more for the cheaper generic. This happens mostly in the U.S. and is called a "copay accumulator." Patients think they’re saving money - but their plan is actually rewarding the brand.

Can generic drugs cause side effects that brands don’t?

The active ingredient is identical, so side effects should be the same. But inactive ingredients - like fillers, dyes, or preservatives - can differ. For most people, this doesn’t matter. But for patients with rare allergies or narrow therapeutic index drugs (like warfarin or levothyroxine), even small changes can cause issues. That’s why pharmacists are trained to monitor substitutions. If you notice a change in how you feel after switching to a generic, talk to your doctor. It’s not always the drug - but it’s worth checking.

Why do some countries have generic shortages?

Shortages happen when the price is set too low for manufacturers to cover costs. China’s VBP program caused this in 2024 with Amlodipine. India’s low-margin exports sometimes lead to supply gaps when domestic demand spikes. Even the U.S. had shortages during the pandemic because manufacturers couldn’t get raw materials. The fix isn’t higher prices - it’s smarter pricing. Systems that guarantee minimum margins (like South Korea’s 15-20% rule) avoid this. When companies can’t lose money, they don’t stop making drugs.

Will global generic policies become more aligned?

Slowly. The International Generic and Biosimilars Association (IGBA) is pushing for mutual recognition of bioequivalence data - meaning if a drug is approved in the U.S., it could be accepted in Europe or Japan without retesting. That could cut approval times by 18-24 months. The EU’s new Pharmaceutical Package hints at this. But countries guard their pricing power fiercely. True alignment is years away. For now, we’re stuck with a patchwork system - and patients pay the price.

1 Comments

Michael Page-15 February 2026

It's not about whether generics work. It's about who gets to decide what 'work' means. The system isn't broken because drugs are cheap-it's broken because profit motives have replaced public health as the guiding principle. We treat medicine like a commodity, not a right. And when you do that, you don't get efficiency-you get exploitation dressed up as innovation.