High cholesterol isn’t something you feel. No chest pain. No dizziness. No warning sign. That’s why it’s so dangerous. By the time you notice something’s wrong, the damage might already be done. Hypercholesterolemia-the medical term for high cholesterol-is silently building up plaque in your arteries, inch by inch, year after year. And it’s more common than you think. In the U.S. alone, nearly 94 million adults have total cholesterol above 200 mg/dL. In Australia, about one in three adults has elevated levels. Most don’t even know it.

What Exactly Is Hypercholesterolemia?

Hypercholesterolemia means your blood has too much cholesterol. Cholesterol isn’t bad by itself-it’s needed to build cells, make hormones, and digest food. But when there’s too much of the wrong kind, it starts sticking to your artery walls. That’s low-density lipoprotein, or LDL. It’s called the "bad" cholesterol because it’s the main driver of clogged arteries.

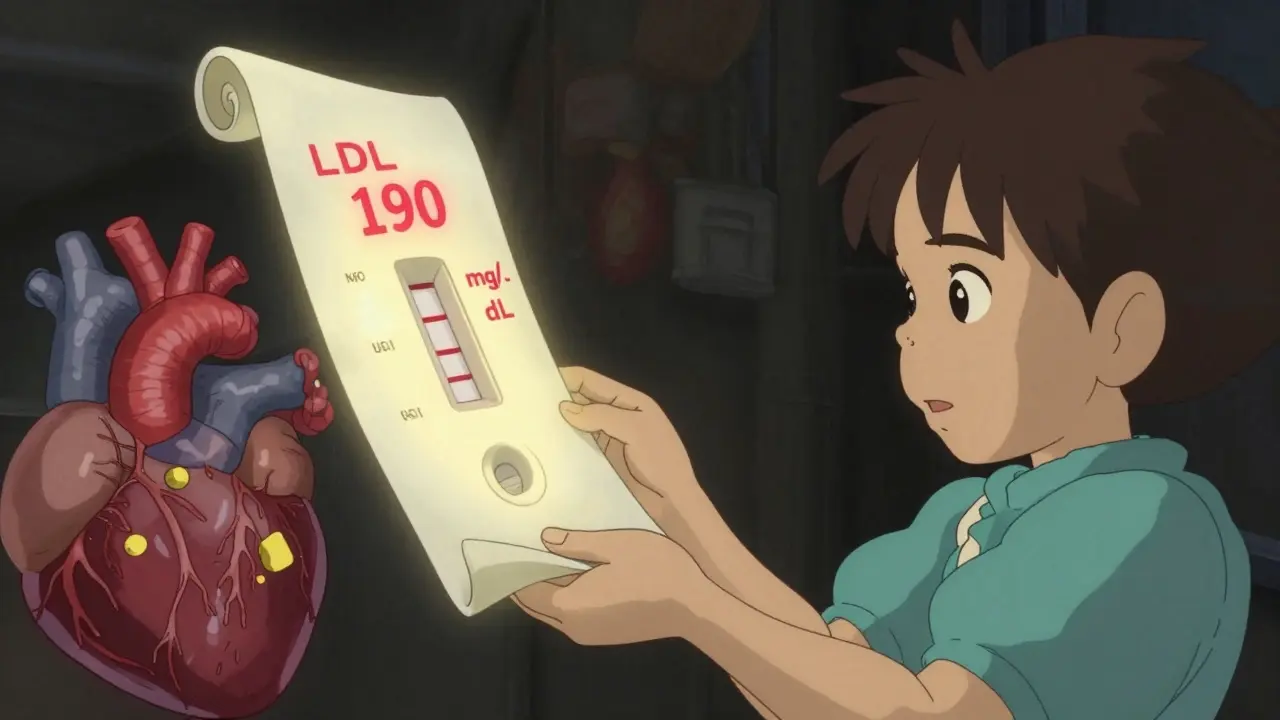

There are two main types of high cholesterol: familial (genetic) and acquired (lifestyle-related). Familial hypercholesterolemia (FH) is inherited. You’re born with it. About 1 in 250 people globally have the heterozygous form, meaning one parent passed on the faulty gene. Their LDL levels are often above 190 mg/dL from childhood. Homozygous FH is rarer-1 in 300,000-but far more severe. These individuals can have LDL levels over 450 mg/dL and face heart attacks before age 20 if untreated.

Acquired hypercholesterolemia is more common. It’s caused by diet, lack of movement, obesity, diabetes, or other conditions like hypothyroidism or chronic kidney disease. This type usually develops later in life and responds better to lifestyle changes. But without action, it can become just as dangerous as the genetic kind.

How Do You Know If You Have It?

You don’t. That’s the problem.

There are no symptoms until an artery is blocked by 70% or more. By then, you could be facing a heart attack or stroke. The only way to know for sure is a simple blood test-a lipid panel. It measures total cholesterol, LDL, HDL (the "good" kind), and triglycerides.

Guidelines now say you don’t even need to fast before the test. That makes it easier. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening for all adults between 40 and 75. But if you have a family history of early heart disease, or if you’re overweight, diabetic, or smoke, you should get tested earlier-maybe even in your 20s.

For most people, LDL should be under 100 mg/dL. If you’ve already had a heart attack or have diabetes, the target drops to under 70 mg/dL. Anything above 160 mg/dL is considered high risk. Above 190 mg/dL? That’s a red flag for familial hypercholesterolemia.

What Does High Cholesterol Do to Your Body?

Over time, excess LDL cholesterol builds up in your artery walls. It triggers inflammation. White blood cells swarm in, trying to clean it up. They get stuck. Fat, calcium, and cellular debris pile up. This is plaque. It hardens. It narrows the arteries. Blood flow slows. Your heart has to work harder. Your brain gets less oxygen. Your legs ache when you walk.

When plaque ruptures, your body tries to patch it with a clot. That clot can block the artery completely. That’s a heart attack if it’s in the heart. A stroke if it’s in the brain. This is why cardiovascular disease kills 17.9 million people every year-more than cancer, diabetes, and accidents combined.

Some people with severe FH develop visible signs. Yellowish fatty deposits called xanthelasmas around the eyelids. Thickened, swollen tendons-especially the Achilles tendon-called tendon xanthomas. These aren’t just cosmetic. They’re physical proof that cholesterol has been building up for years.

Familial vs. Acquired: What’s the Difference?

| Feature | Familial Hypercholesterolemia (FH) | Acquired Hypercholesterolemia |

|---|---|---|

| Onset | From birth | Usually after 30 |

| Typical LDL Level | 190-400 mg/dL (heterozygous); >450 mg/dL (homozygous) | Usually <190 mg/dL |

| Genetic Cause | LDLR or PCSK9 gene mutations | No single gene mutation |

| Response to Diet | Minimal improvement | 10-15% LDL reduction possible |

| Physical Signs | Xanthomas, xanthelasmas common | Rare |

| Heart Attack Risk by Age 40 | 20x higher than average | Similar to general population |

| Typical Treatment | Statins + ezetimibe + PCSK9 inhibitor | Diet, exercise, statin if needed |

The key difference? FH doesn’t care how healthy you eat or how much you exercise. Your body can’t clear LDL properly because of broken receptors. That’s why FH patients need powerful drugs from day one. Acquired high cholesterol? It’s often reversible. Cut out trans fats, eat more fiber, move more, lose weight-and LDL can drop significantly.

How Is It Treated?

There’s no magic pill. But there are proven tools.

First step: lifestyle. The Portfolio Diet-rich in oats, nuts, plant sterols, soy, and fiber-has been shown in clinical trials to lower LDL by up to 30%. That’s as good as a low-dose statin. But most people struggle to stick with it. One study found only 45% were still following it after a year.

If lifestyle isn’t enough, statins are the first-line treatment. Drugs like atorvastatin and rosuvastatin can slash LDL by 50% or more. They’re safe, cheap, and backed by decades of data. The IMPROVE-IT trial showed that lowering LDL with statins cuts heart attacks, strokes, and death by a solid 22% for every 39 mg/dL drop.

But not everyone tolerates statins. About 1 in 5 people report muscle aches. For them, alternatives exist. Ezetimibe blocks cholesterol absorption in the gut. It’s mild-lowers LDL by 18%-but works well with statins. Then there are PCSK9 inhibitors like evolocumab and alirocumab. These are injectables. They cut LDL by another 50-60% on top of statins. They’re expensive, but for FH patients, they’re life-saving.

The newest player? Inclisiran (Leqvio). It’s an RNA-based therapy that targets the liver to reduce LDL production. You get two shots a year. It’s a game-changer for people who forget pills. The FDA approved it in 2021, and it’s now available in Australia under the PBS for high-risk patients.

Why Do So Many People Stay Untreated?

Here’s the hard truth: even when doctors prescribe statins, half of patients stop taking them within a year. Why? Side effects. Fear. Misinformation. "I feel fine," they say. "Why take a pill?"

But here’s what they don’t realize: high cholesterol doesn’t hurt until it’s too late. And once it’s too late, pills won’t undo the damage.

There’s also a gender gap. Women are less likely to be prescribed statins-even when they meet the criteria. Black and Indigenous patients are less likely to get tested or referred to specialists. In Australia, rural patients often wait months for lipid clinics. Access isn’t equal.

And then there’s the diet myth. For years, we were told to avoid eggs and butter. Now, the Dietary Guidelines say dietary cholesterol doesn’t matter much. But that doesn’t mean you can eat fried chicken every day. The real culprit? Saturated fats-found in processed meats, full-fat dairy, and baked goods. And added sugars, which raise triglycerides and lower HDL.

What Can You Do Right Now?

Don’t wait for symptoms. Don’t wait for your doctor to bring it up. Take action.

- Get tested. Ask for a lipid panel. No fasting needed. If you’re over 40, or have risk factors, do it now.

- Know your numbers. Write them down. Know your LDL. If it’s above 160, talk to your doctor. If it’s above 190, insist on checking for FH.

- Eat smarter. Swap butter for olive oil. Choose oats over sugary cereal. Eat beans, lentils, apples, and almonds daily. Limit red meat and processed foods.

- Move daily. You don’t need a gym. Walk 30 minutes. Take the stairs. Park farther away. Movement raises HDL and lowers triglycerides.

- Don’t ignore family history. If a parent or sibling had a heart attack before 55 (men) or 65 (women), you’re at higher risk. Get checked early.

If you’re diagnosed with FH, don’t panic. You’re not alone. But you do need a plan. Work with a lipid specialist. Get on the right meds. Get your kids tested. FH is passed down. One test could save their life.

The Future Is Personalized

Science is moving fast. Polygenic risk scores now let doctors calculate your genetic risk for high cholesterol-not just from one gene, but from hundreds of small variations. This helps identify people who aren’t diagnosed with FH but still have high risk because of their DNA.

And new drugs are coming. Oral PCSK9 inhibitors. Gene therapies. Maybe one day, we’ll fix the broken LDL receptors with CRISPR. But until then, we have what works: testing, lifestyle, and medication.

The goal isn’t perfection. It’s progress. Lowering LDL by 50% cuts your risk of heart disease by half. That’s not a small win. It’s a life-saving one.

High cholesterol doesn’t care if you’re busy, tired, or scared. But you can care for yourself. Start today. Your future heart will thank you.

8 Comments

Benjamin Glover-16 December 2025

Britain’s NHS gets this right-early screening, no nonsense. Americans waste years on ‘diet fixes’ while their arteries turn to concrete. If your LDL’s over 190, you’re not ‘a little high’-you’re a walking time bomb. Statins aren’t optional. They’re mandatory for survival.

RONALD Randolph-17 December 2025

Let’s be crystal-clear: cholesterol isn’t the enemy-bad advice is. The USDA’s outdated guidelines pushed low-fat, high-sugar nonsense for decades-and now we’re paying the price. LDL isn’t the villain; processed carbs are. Eat real food. Move. Stop blaming statins. And for God’s sake, stop eating ‘heart-healthy’ granola bars loaded with corn syrup.

Raj Kumar-17 December 2025

As someone from India, I’ve seen this play out in my family-grandpa had xanthomas, didn’t know why. We thought it was just ‘aging.’ Now I get my lipid panel every year. If you’re South Asian, you’re at higher risk even if you’re skinny. Don’t wait. Eat more dal, less ghee. Walk after dinner. And if your doc says ‘just watch it’-push back. You deserve better care.

Also, inclisiran? That’s huge. Two shots a year? My uncle forgets to take his pills. This could save him.

John Brown-17 December 2025

Really appreciate this breakdown. I used to think cholesterol was all about eggs and butter. Turns out, it’s more about what you’re eating instead of what you’re avoiding. Swapping out white bread for oats and walking 20 mins after dinner changed my numbers. No meds needed. Not everyone needs a drug-sometimes you just need to move and eat like your body actually matters.

Christina Bischof-18 December 2025

My dad had a heart attack at 52. No warning. Just… gone. I got tested last year. LDL was 187. I didn’t panic. I didn’t cry. I just started walking. And eating nuts. And telling my sister to get checked too. It’s not scary if you act. It’s scary if you don’t.

Jocelyn Lachapelle-19 December 2025

I’m 34, healthy, no family history, but I got tested because I read this. My LDL was 172. I was shocked. Now I eat oatmeal every morning. I walk with my dog. I don’t stress about it. But I know now. Knowledge is power. And power means you can change things before they break.

John Samuel-21 December 2025

Let me be unequivocally clear: the notion that ‘cholesterol doesn’t matter’ is a dangerous myth peddled by food corporations and wellness influencers with no medical training. The science is unequivocal-LDL particle count correlates directly with atherosclerotic burden. The Portfolio Diet? Brilliant. But it’s not a panacea. For familial hypercholesterolemia, lifestyle is a supportive cast member-not the lead. PCSK9 inhibitors are not ‘expensive luxuries’-they are biological lifelines. If you’re not advocating for universal lipid screening before age 30 for high-risk groups, you’re not just negligent-you’re complicit.

And yes, emoji: 🚨🩸🧬

Sai Nguyen-22 December 2025

Why do Americans think diet fixes everything? In India, we know: genetics don’t lie. My cousin’s LDL was 420 at 18. He ate ‘healthy’-no meat, no oil. Still died at 24. Your ‘eat more oats’ advice is naive. FH isn’t a lifestyle problem. It’s a genetic emergency. Stop pretending willpower beats biology.