When someone with Parkinson’s disease starts seeing things that aren’t there-voices, shadows, people in the room-they’re not imagining it. This is Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP), a real and common complication that affects about 1 in 4 patients. But treating it isn’t simple. Many antipsychotics, the very drugs meant to calm these hallucinations, can make the tremors, stiffness, and slow movement of Parkinson’s dramatically worse. In fact, using the wrong antipsychotic can turn a person’s daily life into a struggle they didn’t have before.

Why Antipsychotics Make Parkinson’s Worse

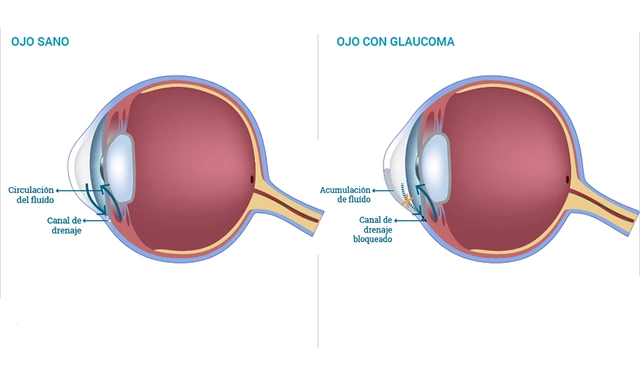

Parkinson’s disease is caused by the loss of dopamine-producing nerve cells in the brain. Dopamine isn’t just about mood-it’s essential for smooth, controlled movement. When those cells die, the brain can’t send the right signals to the muscles. That’s why people with Parkinson’s have tremors, stiffness, and trouble starting to walk.

Antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine receptors, especially the D2 type. That’s how they reduce hallucinations and delusions in schizophrenia. But in Parkinson’s, the brain is already low on dopamine. Blocking what little remains is like turning off the last light in a dark room. The result? Motor symptoms spike.

This isn’t theoretical. It’s been documented since the 1970s. In the 1990s, the American Academy of Neurology first warned doctors to avoid certain antipsychotics in Parkinson’s patients. Today, the data is even clearer: high D2 receptor blockade = high risk of worsening movement.

The Worst Offenders: First-Generation Antipsychotics

Not all antipsychotics are created equal. First-generation antipsychotics (FGAs)-like haloperidol, fluphenazine, and chlorpromazine-are the most dangerous for Parkinson’s patients.

Haloperidol (Haldol) is the classic example. At standard doses, it blocks 90-100% of D2 receptors. Studies show that 70-80% of Parkinson’s patients who take even tiny doses-0.25 to 0.5 mg daily-develop severe worsening of their motor symptoms. Some become unable to walk or speak. In many cases, the damage isn’t temporary. It can linger for weeks or months after stopping the drug.

Fluphenazine and chlorpromazine are nearly as bad. The Parkinson’s Foundation’s 2023 guidelines say FGAs should be avoided entirely. There’s no safe dose. Even if a patient seems to tolerate it at first, the risk of sudden, severe motor decline is too high.

And it’s not just about movement. A 2013 Canadian study found that patients taking risperidone-a second-generation antipsychotic-had more than double the risk of death compared to those not taking any antipsychotic. That’s why many neurologists call these drugs a last resort, not a first option.

The Safer Options: Clozapine and Quetiapine

There are two antipsychotics that have been studied enough to be considered safer for Parkinson’s: clozapine and quetiapine.

Clozapine (Clozaril) is the gold standard. It blocks dopamine receptors only weakly-around 40-60%-and also acts on serotonin receptors, which helps reduce psychosis without crushing movement. The FDA approved it specifically for Parkinson’s psychosis in 2016. In clinical trials, clozapine reduced hallucinations by nearly half without worsening motor scores. One study showed a motor score increase of just 1.8 points on the UPDRS-III scale, compared to 7.2 points with risperidone.

But clozapine has a catch: it can cause agranulocytosis, a dangerous drop in white blood cells. That’s why patients need weekly blood tests for the first six months. If the absolute neutrophil count falls below 1,500 cells/μL, the drug must be stopped. It’s a hassle, but for many, it’s worth it.

Quetiapine (Seroquel) is used off-label because it’s easier to monitor. It has even lower D2 receptor affinity than clozapine and doesn’t require blood tests. Many doctors start with quetiapine at 12.5-25 mg at night. It often works within a week or two. But here’s the problem: some studies show it works no better than a placebo. A 2017 trial found no significant difference between quetiapine and sugar pills in reducing hallucinations. So while it’s safer for movement, its effectiveness is uncertain.

The Other Drugs That Don’t Work

Olanzapine (Zyprexa) and risperidone (Risperdal) sound promising on paper. They’re second-generation, so they’re supposed to be safer. But they’re not.

In one study of 12 Parkinson’s patients on olanzapine, 75% had improved psychosis-but 75% also had worse movement. Half of them got so stiff and slow they had to stop the drug. Risperidone was even worse. In a double-blind trial, risperidone cut hallucinations just as well as clozapine-but it made motor symptoms 4 times worse.

And then there’s pimavanserin (Nuplazid). It was approved by the FDA in 2016 as the first antipsychotic for Parkinson’s psychosis that doesn’t block dopamine at all. Instead, it targets serotonin receptors. Early trials showed no motor worsening. But post-marketing data revealed a 1.7-fold increase in death risk. The FDA added a black box warning. It’s used now, but only when other options have failed-and with extreme caution.

Before You Reach for an Antipsychotic

Here’s the most important thing: most cases of Parkinson’s psychosis can be managed without antipsychotics at all.

Doctors are trained to look at the whole picture. Is the patient on too much levodopa? Too many dopamine agonists? Are they taking an anticholinergic for tremor? These drugs can all contribute to hallucinations.

A 2018 study found that 62% of patients with psychosis improved just by adjusting their Parkinson’s meds-lowering dopamine agonists, reducing anticholinergics, or tweaking levodopa timing. No antipsychotic needed.

That’s why the Parkinson’s Foundation recommends a three-step approach:

- Evaluate the patient’s full medication list and lifestyle factors.

- Adjust Parkinson’s medications first-cut back on the ones that trigger psychosis.

- If psychosis continues, then consider clozapine or quetiapine.

Never start an antipsychotic without trying these steps first.

Monitoring and When to Stop

If an antipsychotic is started, close monitoring is non-negotiable.

Motor function should be checked every two weeks using the UPDRS-III scale. If scores rise by more than 30% from baseline, the drug should be stopped immediately. That’s the rule from the International Parkinson and Movement Disorder Society.

With clozapine, it takes 4-6 weeks to reach full effect. Don’t give up too soon. But if motor symptoms start creeping up after week 3, it’s a red flag.

With quetiapine, effects show faster-often in days. But if there’s no improvement in psychosis after 2 weeks, it’s unlikely to help. Keep the dose low. Don’t push it higher hoping for better results. Higher doses increase the risk of sedation, falls, and confusion.

The Bottom Line

Parkinson’s disease psychosis is real. It’s frightening for patients and families. But treating it with the wrong drug can make things far worse.

The safest path isn’t always the fastest. It’s the one that protects movement first. Clozapine is the most effective and safest antipsychotic for Parkinson’s-but only if blood tests are done regularly. Quetiapine is easier to use, but its benefits are uncertain. All others-haloperidol, risperidone, olanzapine-should be avoided.

And before you even think about an antipsychotic, ask: can we fix this by adjusting the Parkinson’s meds? In most cases, the answer is yes.

For patients and caregivers, the message is simple: don’t rush to antipsychotics. Talk to your neurologist. Review every pill. Push for medication adjustments first. Your loved one’s ability to walk, speak, and live independently is worth more than a quick fix for hallucinations.

13 Comments

Palesa Makuru- 3 January 2026

Ugh, another medical post pretending to be deep when it’s just regurgitating guidelines. I’ve seen this exact thing in Johannesburg - families panic and beg for antipsychotics like they’re magic pills. Meanwhile, the neurologist’s real job is to have the patience to untangle a 12-pill cocktail. But no, let’s just drug the problem away, right?

Hank Pannell- 4 January 2026

What’s fascinating here is the neuropharmacological asymmetry: dopamine depletion in the nigrostriatal pathway versus the mesolimbic hyperactivity driving psychosis. Antipsychotics, by design, are blunt instruments - they don’t discriminate between pathological and physiological dopaminergic signaling. Clozapine’s partial agonism at 5-HT2A receptors may offer a modulatory buffer, but we’re still operating in a space where we’re treating a system’s collapse with a sledgehammer wrapped in silk.

Sarah Little- 5 January 2026

Quetiapine’s placebo effect is so well-documented in PD psychosis that I wonder if we’re just comforting ourselves with the illusion of control. The data’s messy. The trials are underpowered. And yet - we prescribe it anyway. Because what else are we supposed to do? Sit there while someone sees their dead mother in the hallway?

innocent massawe- 7 January 2026

God, this hits hard. My uncle in Lagos had PDP. They gave him haloperidol - he couldn’t stand for a week. We cried. No one told us it was dangerous. Please, someone share this with doctors in Africa. We don’t have clozapine labs. But we have people who need help.

🥺

veronica guillen giles- 7 January 2026

Oh wow. So we’re just supposed to ‘adjust meds’ like we’re tuning a radio? Let me guess - the neurologist’s office is 3 hours away, the patient is 82, and the family is exhausted? You think they’re gonna wait 6 weeks for a titration? Please. This is the kind of ivory-tower advice that gets people locked in nursing homes because no one had the guts to say, ‘We’re out of options.’

Vincent Sunio- 8 January 2026

There is a fundamental epistemological flaw in the premise that ‘adjusting levodopa’ is a viable first-line intervention for psychosis in Parkinson’s disease. The pathophysiological underpinnings of PDP are not reducible to dopaminergic overstimulation alone - they involve cholinergic dysregulation, noradrenergic depletion, and cortical thinning. To reduce therapeutic strategy to a pharmacokinetic tweak is not clinical reasoning - it is reductionist dogma masquerading as pragmatism.

Kerry Howarth-10 January 2026

You’re not alone. I’ve been there. My dad was on risperidone for 3 weeks - turned into a statue. We switched to quetiapine, no blood tests, no drama. He still sees his late wife sometimes… but he can walk to the porch again. That’s the win.

Brittany Wallace-11 January 2026

It’s heartbreaking how little we talk about the emotional toll on caregivers. The hallucinations are terrifying - but so is watching someone you love lose their mobility because a doctor thought ‘it’s just a side effect.’ We need more compassion, not just algorithms. 🌱

❤️

Liam Tanner-11 January 2026

Just want to add - if your neurologist hasn’t mentioned pimavanserin, ask about it. It’s expensive, it’s got the black box, but for some, it’s the only thing that doesn’t turn them into a statue. And yes, the death risk is real - but so is the risk of falling because you can’t move.

Lori Jackson-11 January 2026

How is it that we still let quetiapine be prescribed as a ‘safe’ option when the evidence is essentially null? This isn’t medicine - it’s therapeutic nihilism dressed in a white coat. People are dying because we’re too lazy to do the hard work of tapering dopamine agonists. And now we’re just drugging the symptoms while pretending we’re helping.

Wren Hamley-13 January 2026

Imagine your brain’s a car. Dopamine’s the gas. Parkinson’s? You’re running on fumes. Now someone comes in and slams the brakes - hard - because the radio’s playing too loud. That’s haloperidol. Clozapine? It’s like turning down the volume without touching the gas pedal. Quetiapine? Maybe it just muffles the radio… or maybe it’s just silent. Who knows? But at least the car doesn’t stall.

Ian Ring-15 January 2026

I’m a nurse in rural Oregon - we get 2-3 PD psychosis cases a month. Clozapine? We can’t do the blood work. Quetiapine? Sometimes works, sometimes doesn’t. We’ve had patients improve after stopping amantadine. No one ever thinks to ask about that. Just… give the antipsychotic. It’s easier. But it’s not right.

💔

erica yabut-15 January 2026

Let’s be real - if you’re prescribing anything other than clozapine for PDP, you’re not a neurologist. You’re a pharmacist with a license and a guilty conscience. The rest is just performative medicine for people who don’t want to deal with the mess.